Research at The National Archives in London by our county editor has revealed a possible attempt to make steel in Chesterfield in the period around 1600. We’ll take a brief look at this potentially important discovery in this blog.

The Leakes and the Foljambes

Hidden away in what are called Star Chamber depositions (witness statements taken as part of legal proceedings) taken in 1608 is a reference to what seems to have been an experimental iron mill. The case centred on whether the mill was in Walton or Brampton. At this date Walton manor was held by the Foljambes, and Brampton held by the Leakes of Sutton. The River Hipper formed the boundary between the two. The Foljambes and Leakes were the two leading gentry families in the Chesterfield area in the sixteenth century and it was not unknown for violence to occur where they disagreed!

The last head of the direct male line of the Foljambe family, Godfrey Foljambe, died in 1598, leaving a young widow, Isabel, who married Sir William Bowes of County Durham. There was already an ‘iron mill’ powered by the Hipper on the Foljambe estate, but Bowes claimed in the court case that he had spent £300 building another one.

An experiment in steel making

Witnesses in the Star Chamber case gave conflicting accounts of a dispute between servants of Sir William Bowes and Sir Francis Leake in September 1605, but both sides described the new works as a mill to make ‘steel and iron’. This is an unusual phrase for this date, added to which Bowes is said to have kept the works locked, suggesting that he was experimenting with a new process there. Attempts to make steel were just getting underway around the start of the seventeenth century, in the Sheffield area as elsewhere, and it is possible the Bowes was trying to make steel at the mill on the Hipper, using iron smelted at another iron mill higher up the river. The experiments probably came to an end when Bowes died in 1611, if not before.

The location

In his deposition Bowes stated that when he gained control of the Foljambe estate through his marriage to Isabel there were already six corn mills, one lead mill and one iron mill on the Hipper in Walton. The first of these figures refers to the number of mill stones, rather than separate buildings, but it is clear that the river was already being intensively exploited by industry in the late sixteenth century.

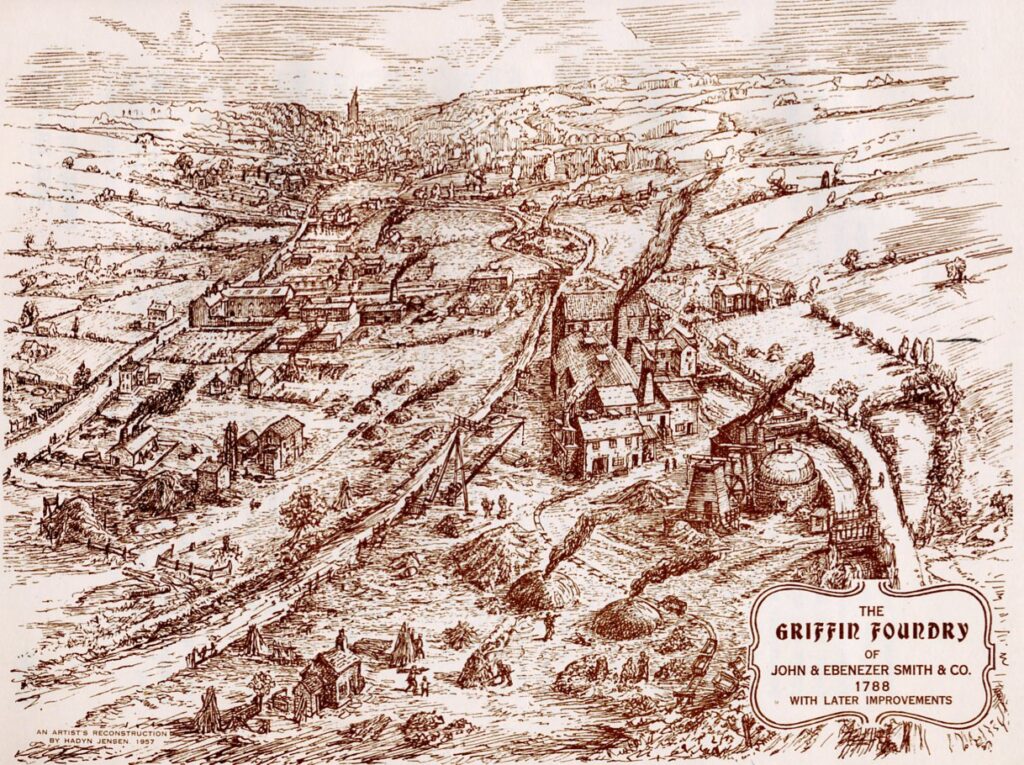

Bowes’s new works stood on a piece of ground called Upper Whitting Holme, which in the 1770s became the site of Ebenezer Smith’s Griffin Ironworks and Francis Thompson’s engine-building forge. The only surviving built from either enterprise is Cannon Mill, built by the Smiths apparently for boring cannon during the Napoleonic War, which ended in 1815. The date 1816 on a cast-iron plaque on the building commemorates its use during the war, not when it was built.

The mills on the river in the early seventeenth century are marked on a map of the Foljambe estate in Walton surveyed in 1622. This marks the mill built by Sir William Bowes downstream from the corn mill, iron mill and lead mill. The corn mill remained in use until modern times and the storage pond which supplied water to this and other mills survives as Walton Dam off Walton Road. One of the other mill sites was later taken over by Hewitt’s cotton mill, which also survives and is one of the very few late eighteenth-century fire-resistant textile mills still standing anywhere in England.

Research on the history of the Foljambe estate at Walton in the early seventeenth century, for which the main source are the voluminous records of litigation in Star Chamber and other courts, is continuing and it is possible that more will be discovered about what Sir William Bowes was trying to do at the iron mill on the Hipper.