Spital Mills History – part 2

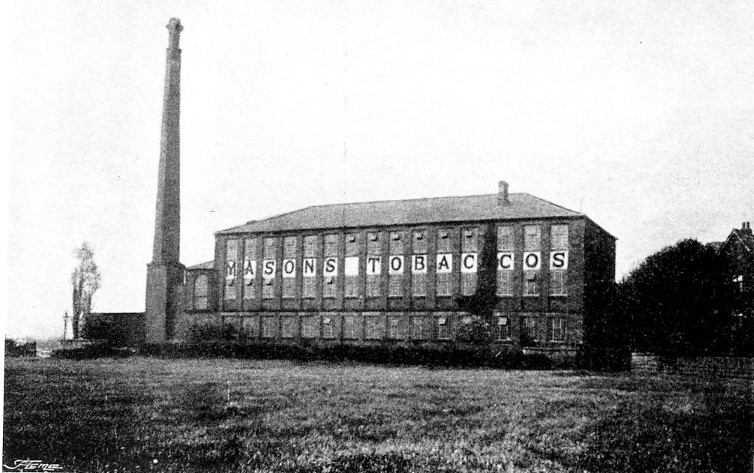

This is part two of our history of ‘Spital Mills’ – more recently known as the premises of Spital Tile. This time we look at the mill as a centre of tobacco manufacturing.

In the early 19th century George Mason, born at Cutthorpe (in Brampton) in about 1794, was a tobacco manufacturer in Chesterfield, with premises at 45–47 and 49–51 Low Pavement (either side of Wheeldon Lane). Here he had a works powered by a horse-gin, making cigars and twist tobacco. He was employing six men in 1851.

Mason died in 1854, leaving personal estate of £4,000, when the business, henceforth known as George Mason & Son, passed to his second son Edwin, born about 1829. He was living with his wife and family in Mason’s Yard, behind Low Pavement, in 1861, when he had 15 men, ten girls and two boys working for him.

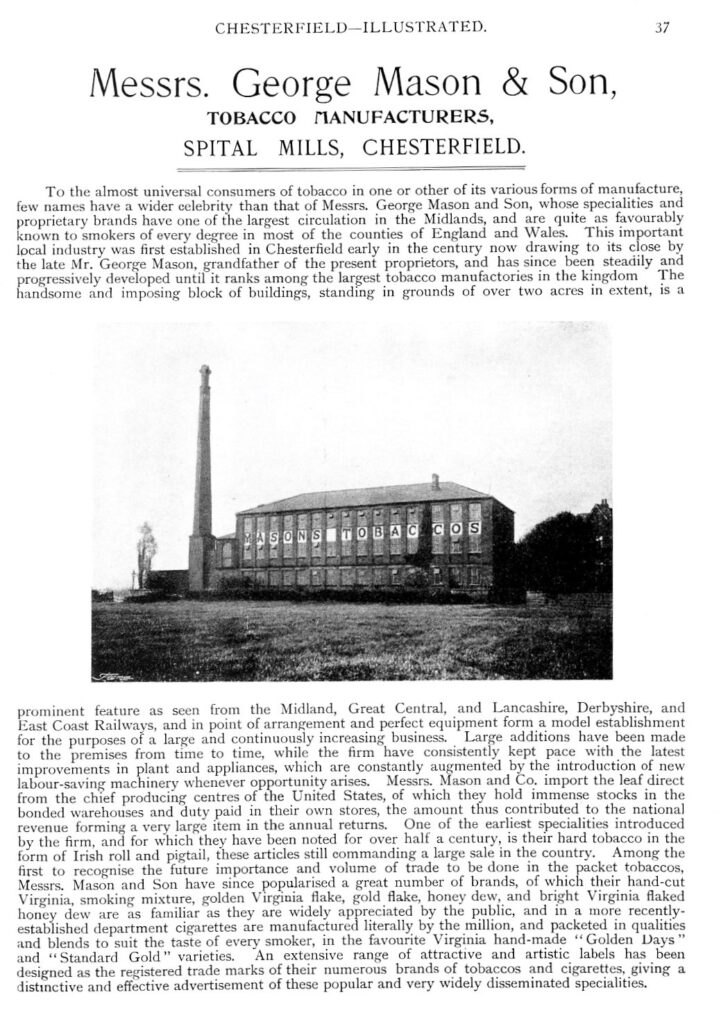

A few years later, as the business grew rapidly, Mason moved to the former lace mill on Spital Lane – our Spital Mills and bought Spital House as a residence. By 1871 he had 116 employees at the tobacco works.

Edwin Mason died in 1887, leaving personal estate of £44,030. He was the sole owner of George Mason & Son, which was described as one of the largest tobacco manufacturers in England. He concentrated on business rather than engaging in public affairs, and was ‘retiring and unambitious’. In the 1880s the company was said to employ more young women than any other concern in the town.

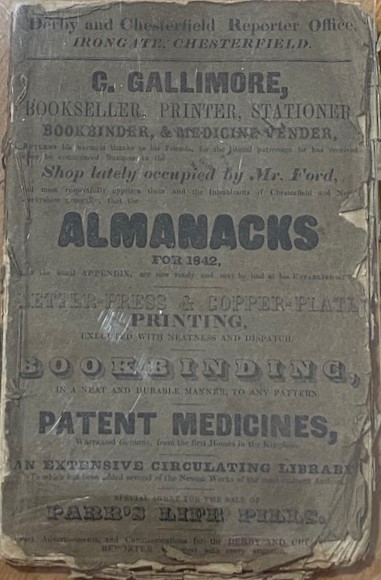

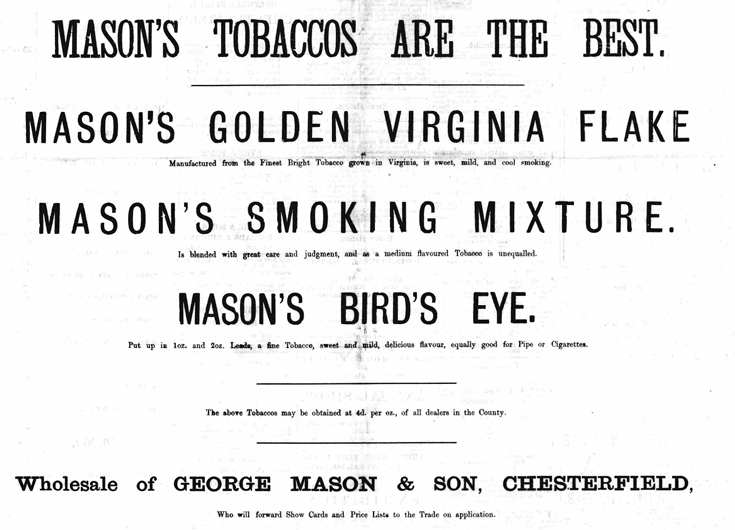

Edwin’s two sons, Oscar Edwin and Charles Leonard, succeeded to the business just as tastes were changing and the demand for twist tobacco was falling. They tried to move into cigarette making, advertising repeatedly over two years in 1892–4 for ‘up to 40 respectable young girls’ to learn the ‘clean and light work’ involved. They also, immediately after their father’s death, rather extravagantly took a half page advertisement in the Derbyshire Courier for several weeks to promote the company. Their final undoing was the creation of a tobacco combine by the larger British firms, in an attempt to meet American competition. Masons were not included and found their old markets closed to them.

Another reason for the decline of what was clearly a very successful company in their father’s day appears to be loss of interest on the part of his sons. Oscar initially lived at Spital House but, after the estate was sold to the Lancashire, Derbyshire & East Coast Railway in the early 1890s, moved to Dunston Hall (in Newbold), where in 1901 he was employing a governess and eight servants, several more than his father ever had.

Oscar remained at Dunston Hall until he died, aged only 45, in 1903, when he left a modest £1,283. An obituary made no reference to his business career, but described him as an enthusiastic sportsman.

Oscar died after returning home early from a race meeting at Doncaster; he and his family were then staying at Bridlington (Yorks.). Many years later it was said that he had ‘always been largely interested in racing and sport’. His widow Mary Ann died at Frimley (Surrey) in 1936.

The business came to an end soon after Oscar died. In 1901 both he and his brother Charles, who was then living with his family, a governess and three servants in a house in The Crescent, Scarborough (Yorks.), gave their occupation as tobacco manufacturer, but Charles was a ‘late tobacco manufacturer’ in 1911, when the family were living in rooms in Cheltenham (Gloucs.) with no servants.

Charles later lived at various places on the South Coast and died at Portsmouth (Hants.) in 1935, leaving personal estate of just £20.24.

This brings to a close the tobacco manufacturing story of Spital Mills – but there is more to come in our next post.

Part one of our history of Spital Mills can be found here.

The next and final part of our history can be found here.

This text is a slightly edited version of that appearing in our ‘History of Hasland …’ book, which is now of print, but you can find copies in Chesterfield Local Studies Library. All sources are fully referenced in our book.

Spital Mills History – part 2 Read More »