An introduction to the Shambles, Chesterfield

There’s a brief introduction to the Shambles area of Chesterfield in this blog. We also dispel the incorrect theory, often repeated, that the area was originally temporary market stalls which became permanent structures over a period of time.

There’s no evidence – as our ‘Chesterfield Streets and Houses’ book states – that the Shambles were originally market trader’s stalls that became permanent buildings over a period of time. It’s worth quoting from our book to give a short introduction to the area.

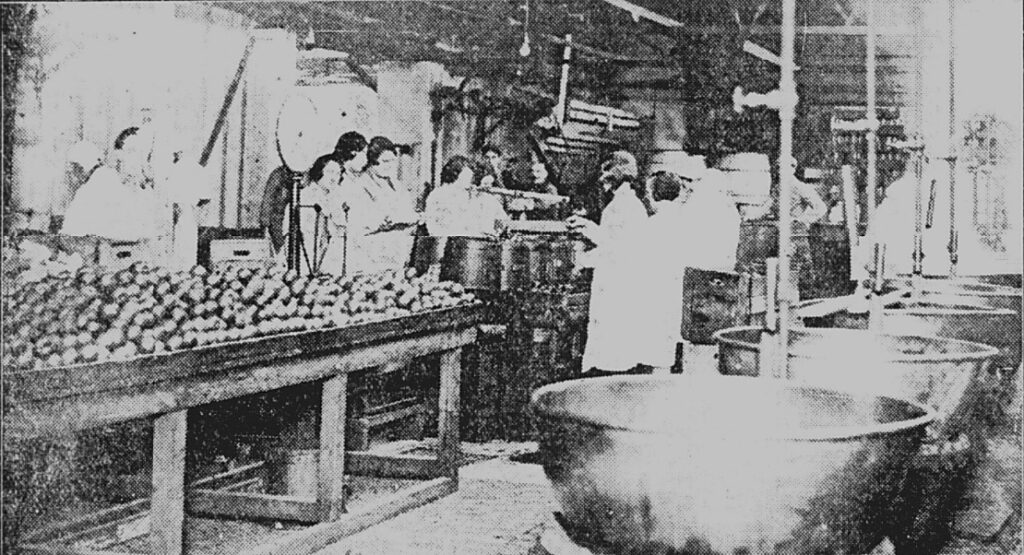

When the New Market was laid out in the late 12th

Philip Riden, Chris Leteve and Richard Sheppard, Chesterfield Streets and Houses, (2019) p. 109.

century, an area at the eastern end of the Market Place

was reserved for a large block of shambles, intended

for butchers, fishmongers and possibly other traders

who would have stood in the market every day, not

merely on Saturdays. The block was bounded on the

east by what is now Packers Row (which appears to

have marked the western limit of the built-up area

before the New Market was created), on the south by

what is now Central Pavement (named by Potter in

1803 as Toll Nook, presumably referring to a place

where tolls were collected at the eastern entrance to the

market place), on the west by the Market Place itself,

and on the north by High Street.

The Shambles were roughly square, and consisted of

a block of small buildings divided into eight groups,

four on either side of a central east–west alley, which

continues the line of Church Lane through to the

Market Place, and presumably follows the route of the

earlier road leading out of Chesterfield to the west

(which today continues as West Bars at the opposite

end of the Market Place). At right angles to this central

alley three others ran from north to south. Six of the

eight blocks of building thus created were probably

originally of the same width (although some variation

has developed over the centuries); the two westernmost

blocks, fronting the Market Place, appear always to

have been somewhat wider, to enable larger buildings

to be erected on a more important frontage. Within the

eight blocks, it is possible that each plot (apart from

those facing the Market Place) was originally the same

size, but by the early nineteenth century, when the

Shambles were first accurately mapped, considerable

variation had developed, presumably as a result of the

amalgamation (rather than division) of the original

plots.

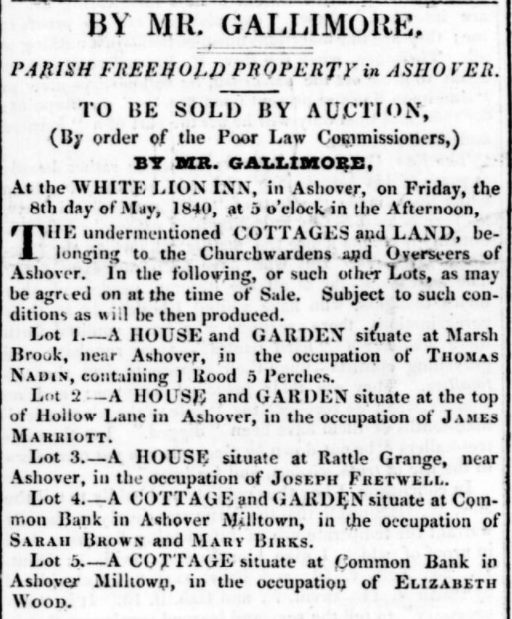

About twenty deeds relating to property in the

Shambles dating from before c.1600 survive…

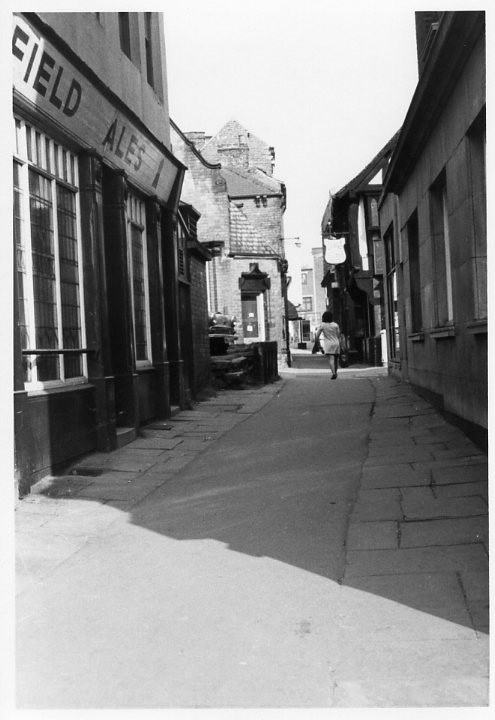

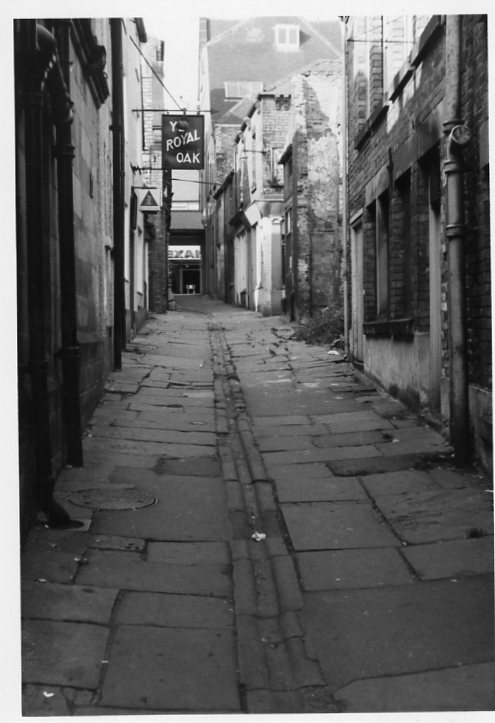

There’s little doubt that parts of Chesterfield had seen better days in the 1970s, including the Shambles. This was undoubtedly due to various schemes for comprehensive redevelopment that (fortunately) fell-through in the mid-1970s. We end this introduction to the area with two September 1973 photographs taken by the late Chris Hollis.

The Cathedral Vaults public house (with its one-time neighbour) was accompanied by three other separate properties facing the Market Place. These were all probably re-fronted in the Georgian period, with pillared arcades on the ground floor. The rear of the Vaults (seen below) was earlier – perhaps 17th century. Only one of these pillared structures survives – that on Low Pavement. The ‘Pretty Windows’ as the Vaults became known was subsequently rebuilt – it’s currently a pharmacy.

An introduction to the Shambles, Chesterfield Read More »