Penmore Hospital, Hasland

In this blog we’ll take a look at the former Penmore Hospital Hasland. What follows is a shortened version of an account in our History of Hasland book.

Beginnings

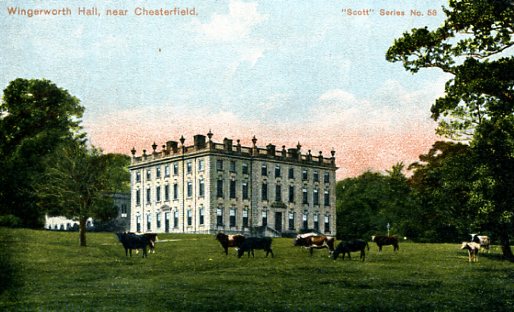

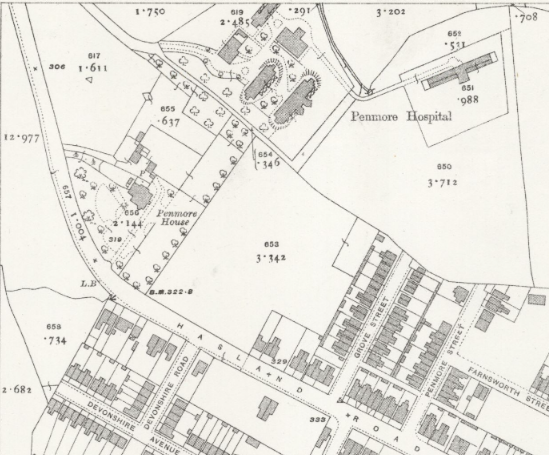

In 1894–5 Chesterfield corporation purchased just over 12 acres of land at Penmore from the duke of Devonshire for an isolation hospital.

Plans for a 30-bed hospital were prepared in 1899 by G.E. Bolshaw of Southport (Lancs.), with construction tenders sought in 1902.

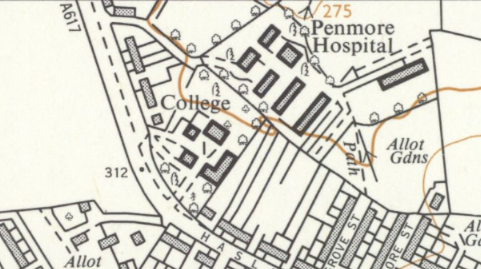

The hospital consisted of several blocks of buildings to the rear of Penmore House. Access was from Hasland Road. The building was opened in 9 December 1904. It was commissioned by the Chesterfield joint hospital committee. An earlier smallpox hospital off Spital Lane was not replaced by this building, which was to continue handling such cases.

Extensions

In 1912 Penmore had 38 beds. 1916 saw extensions, designed by the local architect T.S. Wilcockson, completed at a cost of £9,000. Built of brick with stone dressings to harmonise with the older buildings, the extensions comprised a male ward with eight beds, a female ward with five, and a doubling of the accommodation in the administrative block. Electric light was installed in 1924. In 1922 Penmore had 50 beds for infectious diseases.

After escaping closure during a reorganisation of isolation hospitals in north-east Derbyshire in 1930, the number increased slightly to 59. Six years later the Chesterfield joint hospital committee was dissolved and Penmore isolation hospital, with 58 beds, was transferred to Chesterfield corporation.

In 1942 a scabies cleansing station was established at Penmore by the corporation.

Post-war reconstruction and refurbishment

The rest of the buildings appear not to have been used as a hospital during the Second World War, since after they passed to the National Health Service in 1948 they had to be repaired before the wards could be reopened. From that date Penmore was one of several hospitals, in addition to the Chesterfield Royal, administered by the Chesterfield hospital management committee. In 1945 Penmore was said to consist of old buildings on an uneven site subject to mining subsidence and lacked a resident medical officer.

The first of three blocks at Penmore, containing 35 beds, was ready for use in May 1951, when the rest of the hospital was expected to be completed by August. The Sheffield regional hospital board determined that Penmore would be used for long-stay orthopaedic and medical cases. With authorised accommodation 25 for 60 beds, the hospital had 12 patients in June 1951 increasing to 45 in November.

A 1950 scheme by management committee proposed to purchase Penmore House as accommodation for residential staff did not go ahead. Instead the former tuberculosis pavilion adjoining the hospital was adapted to become a nurses’ home. In 1953 Penmore House (not to be confused with the adjacent Penmore Hospital) was taken over by Chesterfield College of Art.

At the hospital there were problems with subsidence in 1952–4, for which the National Coal Board accepted liability. In 1952, after an inspection by the General Nursing Council, Penmore was accepted as a training centre for nursing assistants, subject to certain conditions, which the management committee undertook to meet. These included the improvement of sanitary accommodation on the wards, the provision of fridges in ward kitchens and the creation of day rooms for patients.

The training school opened until 1956, when a nurse-tutor was appointed (who had herself to take a training course). The first intake of ten students was admitted in January 1957.

The training centre moved to Spring Bank House in Chesterfield at the end of 1961, when the accommodation at Penmore was briefly used as a chapel and later became a patients’ day room.

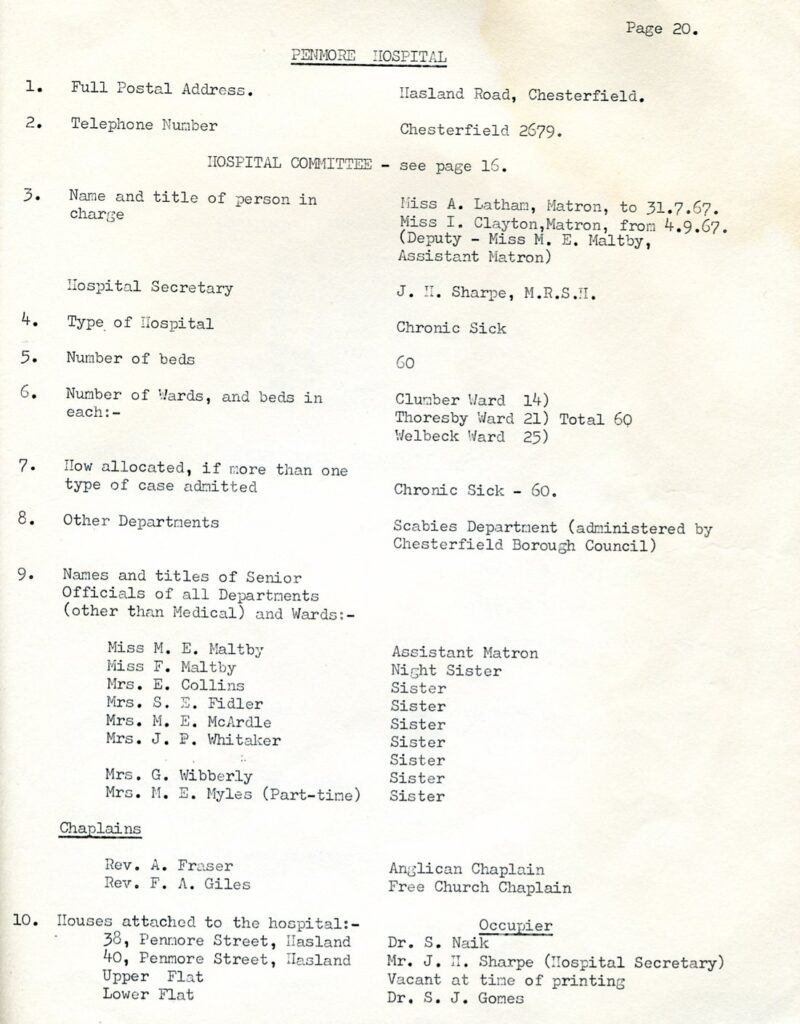

Staffing

1952 saw the staffing levels set for the hospital were a matron, assistant matron, night sister, three ward sisters, three staff nurses and 14 enrolled auxiliaries. There were also 28 non-nursing staff. Twelve months later the hospital lost a ward sister and a staff nurse and was given five orderlies instead; the non-nursing staff was reduced to 20.

When another ward was opened in 1954, an additional sister and staff nurse were appointed, together with four enrolled auxiliaries and two orderlies. In 1954 the hospital had difficulty recruiting nursing staff and remained heavily reliant on overtime working for several years.

The first matron retired in 1957. When her successor was appointed the nursing establishment was increased to 29, including (in addition to the matron, assistant matron and tutor) a night sister in sole charge, three ward sisters, four staff nurses, 12 state enrolled nurses, four pupil assistants and two auxiliaries. The hospital then had just under 50 patients.

When the last ward to be refurbished opened in 1958 the figure rose to about 60. In 1960 Penmore had accommodation for 60 chronic sick cases. By this date the ‘blocks’ of the old isolation hospital had been named Clumber, Thoresby and Welbeck wards and efforts made to improve the grounds.

Gifts

In 1956 staff at the Chesterfield Co-operative store raised funds to present television sets for two of the wards, for which they were warmly thanked, as were 15 students of the college of art who provided Christmas decorations.

From 1958, when £123 was raised, a sale of work was held every summer. By 1963 these events had raised a total of £1,232 for the hospital.

Successive rectors of St Paul’s, Hasland, served as hospital chaplains from 1951, joined by a minister from Hasland Methodist church from 1958.

Declining years

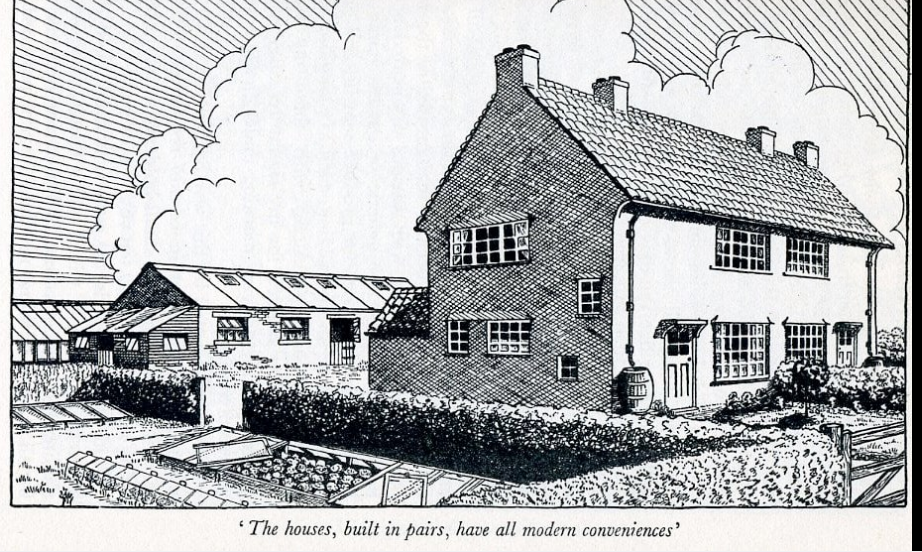

In 1962 student nurses from the Royal Hospital were accommodated in the former administrative block at Penmore. In this period the NHS also owned a pair of semi-detached houses, 38–40 Penmore Street, acquired with the hospital, which were generally let to junior medical staff, as were two flats in the old pavilion, part of which was demolished in 1962.

In 1967 the use of the administrative block as a nurses’ residence was thought likely to be reduced in the near future. The following year the regional hospital board suggested that surplus land at Penmore might be sold. Despite these signs of decline, in 1972–3 a new dayroom was built at the hospital, sanitary facilities improved, and colour televisions bought for the wards.

After the opening of the new Chesterfield & North Derbyshire Royal Hospital at Calow in 1984, Penmore was retained as a 60-bed geriatric unit. It continued to be used in this way in 1987, when it was planned to be run down to closure in 1994.

After the hospital closed, the buildings were demolished and the land sold for housing. The houses on Penmore Street passed into private ownership.

Sources used in this blog

All the sources used in this blog are fully referenced in our History of Hasland book. Although this book (published in 2022) is not now in print, copies can be consulted in Chesterfield local studies library.

Penmore Hospital, Hasland Read More »