Coalite, Bolsover

In this post there is information about the former Coalite smokeless fuel works at Bolsover. The works are now largely disappeared – they have been built on by warehousing and industrial units. This is the first in an occasional series of posts (albeit updated) which originally appeared on our now defunct England’s Past for Everyone website.

Beginnings

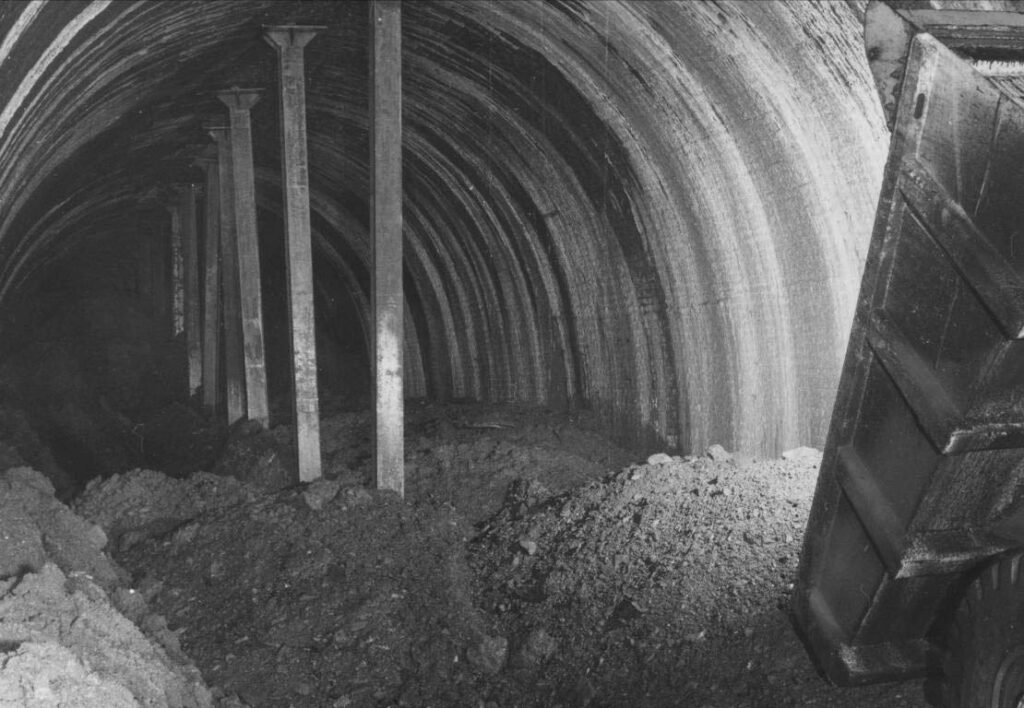

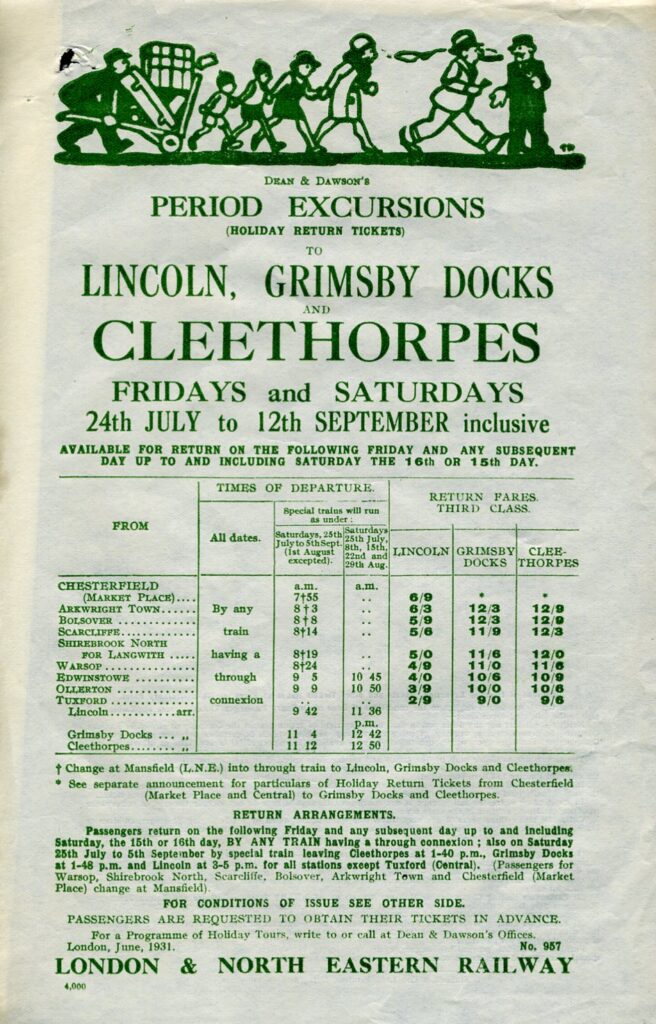

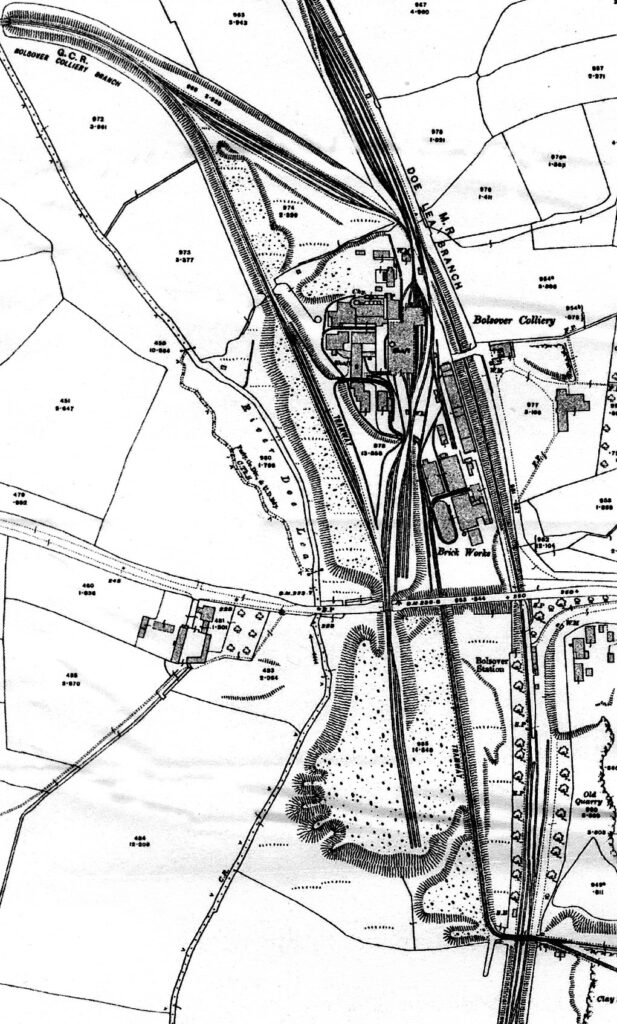

In 1936 the Derbyshire Coalite Company Ltd, a subsidiary of Low Temperature Carbonisation Ltd, decided to erect a plant comprising eight batteries of retorts to make Coalite (an early form of smokeless fuel) on a site to the west of Bolsover colliery. The Bolsover company agreed to supply coal to the plant and was given the right to nominate two additional directors to the Coalite board. Two years later an associated company, the British Diesel Oil & Petrol Co. Ltd, opened an extensive chemical works on an adjacent site to refine the liquid products arising from the treatment of coal by the Coalite process.

Production at the plant began in November 1936 and the site was officially opened by the duke of Kent the following April. It was then using 500 tons of coal a day from Bolsover colliery, thus securing the jobs of 400 miners; 200 men were employed in the carbonisation plant and about 120 on the by-products side.

Full orders

In 1938 it was reported that both the government and local authorities had placed large orders for Coalite, and that the Bolsover plant was working at full capacity. A research laboratory had been opened at the works. In its early years the Bolsover plant also played a leading part in attempts to manufacture petrol and diesel road fuel and oil from coal: the refinery operated by the British Diesel Oil & Petrol Company was in full production in 1939 and working at maximum capacity the following year. The Coalite and by-products plant at Bolsover was then valued at £264,000 and the refinery at £180,000.

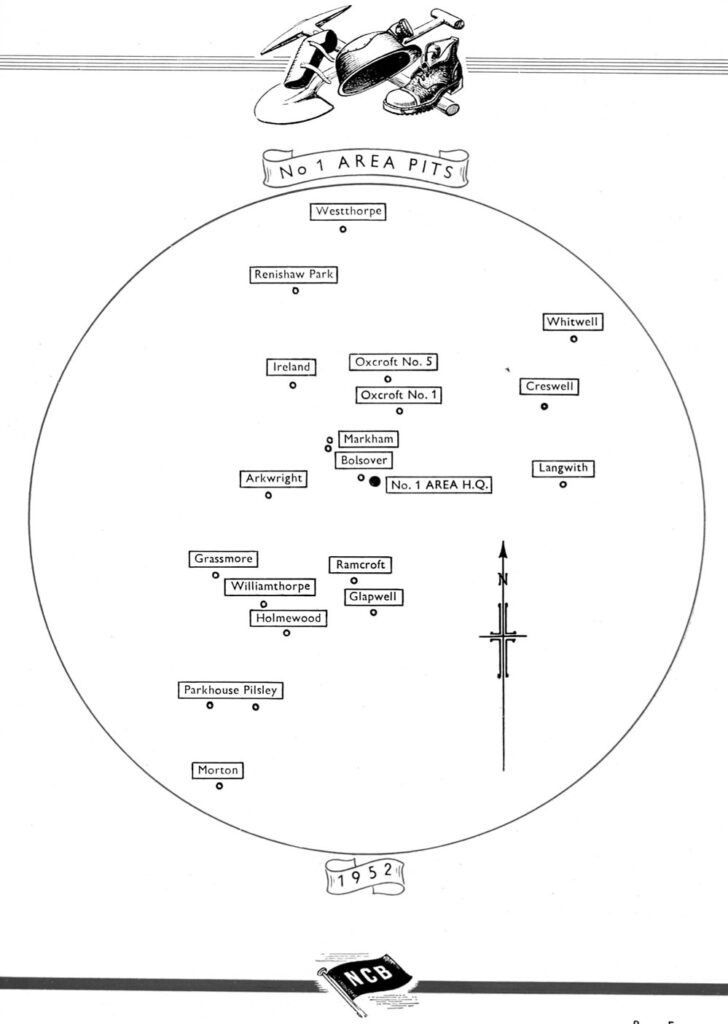

Low Temperature Carbonisation’s activities did not fall within the scope of the Coal Industry Nationalisation Act of 1946, as the minister of fuel and power, Emanuel Shinwell, made clear when he visited the Bolsover plant in May that year. In 1948, however, the holding company was renamed Coalite & Chemical Products Ltd, which continued to operate the Bolsover site through two subsidiaries, Derbyshire Coalite Co. Ltd, responsible for the smokeless fuel plant, and the British Diesel Oil & Petrol Co. Ltd, which ran the distillation plant, refinery and chemical works. In 1952 the registered office for all three companies was moved from London to Bolsover.

The company prospered during the economic growth of the 1950s and early 1960s. In 1953 Coalite ceased to be rationed, although supplies of coal were disrupted that year because of the failure of the Deep Hard seam at Bolsover. In 1956 it was reported that the Coalite plant would shortly have 19 batteries of retorts in use and that there had been a corresponding extension to the chemical plant. When the Clean Air Act came into force the same year Coalite was made an `authorised fuel’ that could be burnt in domestic grates.

Change

In 1960–1 a new research centre for the company’s chemical and chemical engineering activities was built at Bolsover and in 1966 a new wing was added to the head office to house a computer. In addition to the Bolsover plant, where the refinery business was now being run by Coalite Oils & Chemical Ltd, the company was making Coalite at Askern, near Doncaster (Yorks.). In 1972 Coalite employed over 1,200 men in Bolsover.

In 1978 Coalite & Chemical Products was absorbed into Charrrington Industrial Holdings Ltd, whose activities were said to lie mainly in the distribution of solid and liquid fuels, although the group also owned the manufacturers of Dormobile camper vans and the Falklands Islands Company. Three years later what was now the Coalite Group PLC, chaired by Eric Varley, the former Labour Cabinet minister and NUM-sponsored MP for Chesterfield, reorganised its two operating companies into one, Coalite Fuels & Chemical Ltd, which took over the Coalite plants at Bolsover, Askern and Grimethorpe, and the refinery at Bolsover. The Askern plant was closed in 1986. Three years later Varley led an unsuccessful campaign against the takeover of Coalite by the Anglo-United group.

Run-down

Under Anglo-United the Bolsover plant began to contract. In 1991 26 jobs out of a total of 388 at the site were lost, the company pointing to a recession in the chemicals industry and in particular the reduced demand for agrochemicals. Anglo-United also sold the Falkland Islands Company that year, to provide funds for its mainstream activities in solid fuel manufacture, fuel distribution and chemicals.

Health and environmental issues

By the 1990s the owners of the Bolsover site were operating in a much more hostile environmental climate than a generation earlier. As early as 1973 the company’s doctor, a Bolsover GP, had defended conditions at the plant, claiming that cases of chloracne among workers and their families arising from the absorption of dioxins were due to men `not availing themselves of the high-grade personal hygiene facilities at the works’. In 1981 a county council tribunal investigating the long-term effects of an explosion at Bolsover in 1968 found dioxins in opencast coal and clay workings in various places in north-east Derbyshire, although once again the company’s doctor claimed that exposure to dioxins among workers at the plant had no significant long-term effect on their health, apart from persisting minor chloracne in some cases. An article in a trade magazine the same year pointed out that the 1968 explosion had killed one man and left 79 others with severe chloracne. It also drew attention to buried dioxins at Carr Vale and Stretton, where a former clay pit was owned by Cambro Waste Products, one of whose directors was then chairman of Coalite.

Although a report commissioned by the district council in 1989 concluded that most pollution in Bolsover was caused by domestic fireplaces, and another two years later by HM Inspectorate of Pollution was inconclusive, by 1992 the county council was demanding an inquiry into the plant and the National Rivers Authority was taking the company to the Crown Court over dioxin levels in the river Doe Lea near the works said to be 1,000 times higher than normal. MAFF was also concerned at dioxin levels in milk, eggs, meat and herbage around Bolsover, and in 1992 the National Union of Farmers planned to sue Coalite on behalf of three of its members who had been banned from selling their produce for eighteen months after their land had been found to be contaminated.

In 1993 the company opened a new incinerator at Bolsover but continued to be pursued by both Greenpeace and HMIP. In 1995–6 Coalite Chemicals Ltd pleaded guilty to charges brought by the Inspectorate and were fined £150,000 with £300,000 costs; the judge commented that he had taken into account the fact that the company had incurred a great deal of odium locally, probably out of all proportion to the actual risks created by the events leading to the prosecution.

Final phase

The long struggle between environmental concerns and a wish to retain industrial jobs in a district from which most had disappeared entered its final phase after the turn of the century.

In January 2000 Coalite Smokeless Fuels (the trading name of Coalite Products Ltd) announced the loss of 62 manual and eight office jobs from a workforce of 350, blaming the mild winter and investment in new plant. A year later the Environment Agency issued an enforcement notice against the company after several hundred gallons of coal oil were released onto neighbouring land. When the plant changed hands in 2002 the new owners announced a reduction in the output of solid fuel and investment in oil production and a tyre-recycling plant. The company went into administration in 2003, the administrators blaming `unresolved difficulties’ with the Environment Agency over the recycling plant, despite the investment of over £4 million since the change in ownership, and pointing out that nearly 200 jobs were at risk. Although the county council approved plans to extend the tyre recycling operation and oil production the administrators failed to find a buyer and in June 2003 announced the loss of a further 70 jobs at the chemical plant in addition to the 82 lost from the smokeless fuel plant two months earlier.

Coalite Products Ltd appointed receivers in April 2004, who in September that year, having also failed to find a buyer for the company, closed the Bolsover site.

Regeneration

After remaining partially derelict the coking and chemical site has been decontaminated and regenerated, particularly over the last few years. During this work the once-familiar coal-tar ‘Coalite’ smell appeared again, perhaps for one last time. At one stage housing was suggested for part of the site, but since the early 2020s most of it is being progressively built on for industrial and warehousing use, after remnants of the former activity were cleared. Both the chemical and coking plant site is now being marketed as ‘Horizon 29‘.

Sources used in this account (except that in the last section) are fully referenced in our Derbyshire VCH Volume III Bolsover and Adjacent Parishes.