County bridges in the spotlight

The subject of county bridges may not sound over-exciting – but they formed a very important part of the county’s transportation infrastructure – and many still do. A recent publication by Philip Riden (who is also our VCH county editor) – ‘Derbyshire county bridges 1530-1889’- published by the Derbyshire Record Society, puts them in the spotlight, perhaps for the first time in recent memory.

The book contains a gazetteer of 139 county bridges across Derbyshire. As an example, in the Chesterfield area county bridges included ones at Hagg Bridge, Tupton; Stony Bridge, Hasland, Spital Bridge, Hasland; Tapton Bridge; Old River Bridge, Brimington and Whittington; Slittingmill Bridge, Eckington and Staveley and three others on the river Rother alone. On the Hipper were Walton Bridge and Lordsmill Bridge.

What were county bridges?

The Bridges Act of 1530 required the court of quarter sessions (local courts traditionally held at four times of the year) to repair bridges in its county or borough for which no-one else was responsible. In Derbyshire the Act was applied with some vigour. By 1729, when the first list of bridges was compiled, the county was maintaining some sixty bridges, including most of those on main roads in Derbyshire. Between then and about 1840, when the railways began to remove long-distance traffic from the roads, the number of county bridges in Derbyshire roughly doubled. During this period many were rebuilt and widened, and several fine new bridges were erected, which remain in use today. This work was undertaken by a succession of county surveyors, who evolved from working stonemasons into professionally qualified officers. All the bridges passed to the county council on its establishment in 1889.

The county bridges book

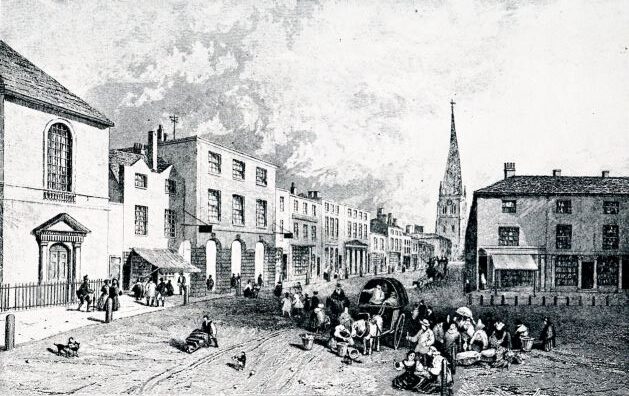

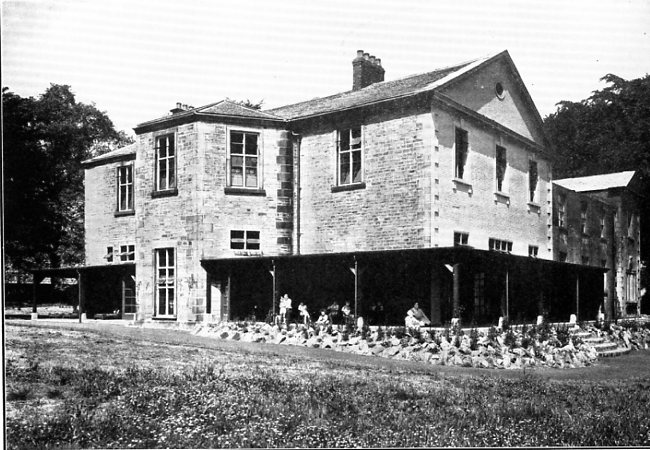

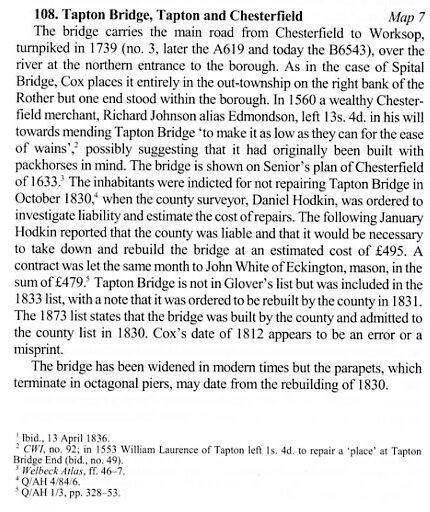

To give a flavour of the book we’ve included an extract from the gazetteer which covers Tapton Bridge on the river Rother. Our illustration above shows the area in the 1980s.

The bridge was one of number rebuilt by the county council in the post-First World War period https://picturethepast.org.uk/image-library/image-details/poster/dccc002544/posterid/dccc002544.html has a picture of the bridge being widened.

The county bridges book is based on bridge papers which survive from the late seventeenth century in the records of quarter sessions at Derbyshire Record Office, Matlock. Described are about 130 bridges in Derbyshire, ranging in date from the thirteenth century to the early nineteenth. All the bridges are located on a series of maps, with a representative sample illustrated. A gazetteer is prefaced by a 36-page introduction outlining the work of quarter sessions under the Bridges Act of 1530 and later legislation. Also included are the careers of the county surveyors.

The Derbyshire Record Society was established in 1977. It publishes edited texts, monographs and pamphlets relating to the history of the county. As you might expect VCH uses a number of these in our work to produce new histories of Derbyshire communities. Find out more about the society at https://derbyshirerecordsociety.org/index.php.

We are particularly grateful to the Derbyshire Record Society and to Philip Riden for permission to use an extract from the book ‘Derbyshire County Bridges 1530-1889’ and to use a description of county bridges in this blog. Copies of the book are available at £33 for non-members (£20 for members of the Derbyshire Record Society) by downloading the order form at https://derbyshirerecordsociety.org/order.php

County bridges in the spotlight Read More »